EXHIBITION - AFTERMATH - JOHN MURRAY

whatiftheworld (Johannesburg)

– Text by Natasha Norman

The process of representation throws the artist into the dual delights of (1) succeeding in creating the illusion of form and (2) the material act of making. It is the latter of these two delights that South African painter, John Murray, foregrounds in his latest solo exhibition, Aftermath. The works on show are held in a tension between figuration and abstraction. Forms drawn from the world are fragmented through Murray’s treatment of paint and pictorial space so that the riddle of the work exists somewhere between a pure Modernist formalism and representational landscape. The title, Aftermath, as per it’s dictionary definition, implies that the works are both a second yield as well a post-apocalypic reality of some great disaster.

It is Murray’s laborious layering of paint that reveals the relationship between the catastrophic and the fertile picture plane. A loose, organic groundwork is worked over with the meticulous and tireless diligence of masked painted forms such that each work records a complex palimpsest of the painter’s industry. In their final state the paintings could allude to peeled commercial signage, the rusted machinery of rural labour or a satellite view of human settlements. The fragments of form that Murray provides engages a game of imaginative reconnection with the objects and surfaces of one’s surroundings.

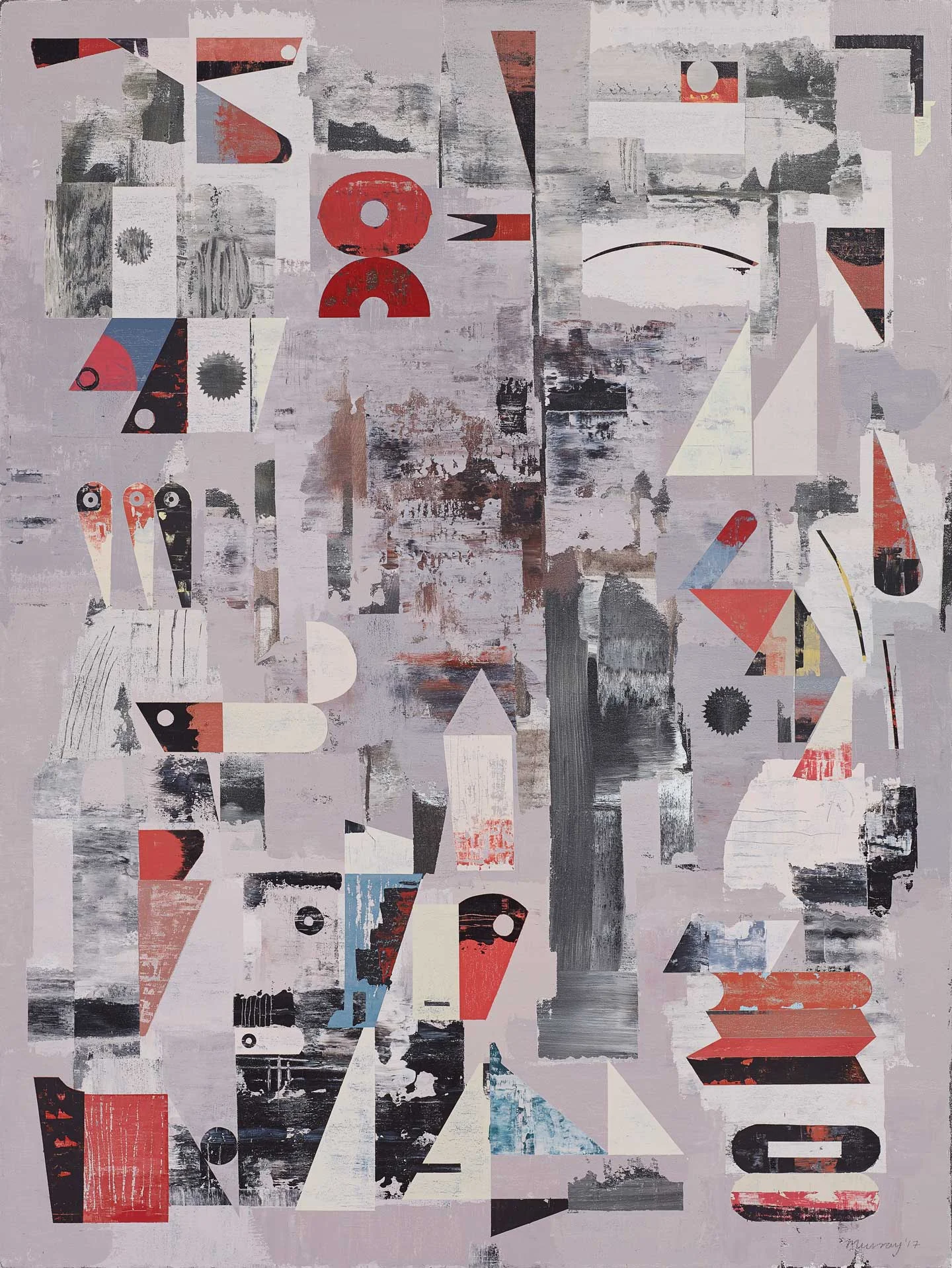

PIPE DREAMS

2017

Acrylic on canvas

120 x 90 cm

The deconstructivist influences of Murray’s formative years as a design and fine art student in the 90s, and subsequent frustration with formal representation has led him to a more subconscious engagement with the painted surface. The tireless actions and reactions imbedded in each painting mark the works as complex signifiers of a unique Formalism based on a South African experience, reflecting a society in the constant state of revolution or reform. The juxtaposition of forms and surfaces, while accumulative, simulaneously speak to the breaking down of a comfortable way to look at or ‘see’ the works.

Aftermath brings the conceptual thoughts about Murray’s surfaces into the immediate present. As an artist living and working in a post-apartheid society that has been both dismantling the Apartheid system whilst developing a new social model, Aftermath is also a processional engagement with systemic deterioration and renewal through the sheer hard work of painting itself. As viewers we are left to contemplate the losses and gains of a practice of image-making guided by intuition, aiming for a place of stillness that never seems to come.

Photo - Oliver Kruger

You have gone through some major changes over the years, from more illustrative-type objects to portraits, and now a mixture of minimalist shapes. Was it an intentional evolution over the years or did it just develop naturally on its own?

I think it has been a bit of both. I started studying graphic design at the university of stellenbosch and changed to fine art after two years. It was quite a radical shift for me and I always felt very torn between design and painting. This has had an influence on how my work has evolved.

Initially the abstract works served as an escape from figurative painting, but what used to be a schism has become more of a symbiosis. For me these paintings function in a space of disorientation, falling short of being fully representational or coherent.

Your last two exhibitions have stuck to the same abstract nature regarding the color and feel and size. Do you feel you have reached a place where you can settle for a while?

A yes in a way, but then again change is integral to everything. I think one always wants to improve or develop. I am never really satisfied after completing a painting. I always think about how to approach the next work differently. I think the figurative work might come to the fore again. It won’t replace the abstract paintings though.

Your use of color is a lot bolder then your earlier pieces, with a mixture of primary and pastels layered across the canvas. What draws you towards certain colors and the way they communicate with each other?

Colour is an incredibly complex phenomenon. I find it very difficult to restrict myself to certain colours. I often set out to make a painting using specific hues or tonal values only to realise that I have gone through the whole spectrum. I think this adds to the “frantic” quality of some of the abstract paintings, where colours compete like they would in a supermarket.

Would you consider doing a portrait series again or do you only do them on commission these days?

I am always thinking about the portrait. It is almost an intuitive reaction that I have when I stand in front of a canvas – to want to make a portrait. Portraits are very specific things, because inevitably they deal with identity. In a south african context it is difficult to make a portrait that is apolitical. In the past I often made portraits thinking I was dealing with identity, but I realise I was quite naïve in my approach. I think these days I am more interested in the portrait as something elusive or even abstract.

“I think it must be very fulfilling as an archaeologist to filter through the artifacts and remains of history.” In a sense I feel you have been similar to an archaeologist with your found objects and broken shards in some of your earlier works such as “objects of unimportance” and “patterns with meaning”.

Yes, I think these works illustrate my fractured way of looking at things. I like the idea of sifting through various objects, shards and images in search of something tangible, but unlike the archeologist my work doesn’t reach a conclusion.

Do these found objects relate to each other?

Yes, but I think it is often quite subtle or not important. I like the idea that there is flux and that the meaning can’t really be pinned down.

Some of your portraiture leaves a hint to some of peter blake’s work in the 50s. Which artists do you feel have been crucial to the development of your work?

It is difficult to answer, because there have been so many at different stages. I have always looked more at figurative painters than abstract painters and specifically at art with a strong graphic quality. As a student I was influenced by the photomontage work of the russian constructivists and artists such as hannah höch and john heartfield. I have also always identified with the tactile qualities of ‘outsider art’.

During 2014’s design indaba you had the opportunity to work with the master carpetmaker paco pakdoust when he did a series of woven carpets using local contemporary artists’ works. How did the collaboration come to life and is it something that you would consider doing again?

It was a collaboration initiated by southern guild. Initially I thought the painting would be too ‘busy’ for a rug, but it worked really well. Southern guild and paco must really get the credit for that.

Some artists reach a point or a safe place and then only produce a certain signature style of work. How do you see your work evolving in the future?

It is difficult to look too far into the future, but as mentioned I would like to bring the abstract and figurative works closer together.

Do you still work with charcoal much these days?

I still work with charcoal. I am in the process of doing a series of charcoal works on paper. It is a medium entrenched in me, due to the many hours spent in the drawing studio as a student!

When you get asked to do a commissioned piece, how much control do you have over what goes into the work in the end in terms of color and arrangement? Is it similar to a designer working with a client or are you open to interpret as you see fit?

A commission can have parameters. I think it is important to keep the ‘client’ in mind, but most importantly to stay true to your own work. It is really up to the artist to establish those boundaries right from the start.

Regarding your work process – do you work on multiple pieces at the same time or do you finish them one by one. Do you find that they cross-pollinate themselves in a way?

I work on multiple pieces at once. It helps me not to get too sucked into one work. It is also practical to work on something else while waiting for paint to dry.

Are you only represented by whatiftheworld gallery now or do other galleries also deal with some of your pieces?

At this stage I am represented by whatiftheworld only. They really put a lot of effort into their artists, so I feel very happy to be represented by them.

Some of your sketchbook work leans very much towards the satirical ‘bitterkomix’ style of anton kannemeyer and conrad botes. Were you in influenced by the whole era at the time and do you still spend a lot of time working on similar illustrations?

Initially as a design student anton and conrad were lecturers of mine and later became friends. They exposed me to illustration and comics and I think a lot of students were energized by the stuff they were doing. I definitely learnt a lot from them especially in terms of drawing. The best teachers are those who teach through their own work and they were definitely doing that.

What do you find the most challenging part of the creative process while you are working on new concepts?

Staying committed to the process. It often takes a long time to complete a body of work and self-doubt is part of that process. It is important to learn to deal with that, especially in the insular confinement of a studio.

AN INTERVIEW WITH JOHN MURRAY

by Michael Smith

John Murray, whose works can often seem like a babble of stimuli, paints indecision, failure and information glut as if they were physical things. His works take on abstraction, and thereby some of painting’s heavyweight thinkers, with disarming humour and lightness. Yet they explore not so much a crisis of representational art, or a jostling between representation and abstraction, as a state of parity between modes of painting, the fertile moment when the hierarchy flattens out and the artist can respond to the needs of the work outside of stylistic strictures.

Photo: John Murray by Guy with a Camera

Michael Smith: Failure is so interesting, isn’t it? I mean, in the context of all we do to puff ourselves out, to compete and scrabble for a living, the admission of failure can be that moment of release we paradoxically crave. The works in your 2013 exhibition ‘Ecstatic Entropy’ were positioned as ‘fai[ling] in their task... [in] attempting representational gestures toward landscapes, structures or symbols...’ How liberating was it to use the notion of failure to frame a conceptual project?

John Murray: Yes, it was quite liberating. I have in the past often struggled to define my specific interest or what I was communicating. I saw that as failure and even stopped producing art for a few years. It used to be quite debilitating, but now I have chosen to embrace it as something potentially interesting. I have made peace with the fact that my paintings are conceptually elusive and rather enjoy functioning in a sort of liminal space. I am deliberately pushing aspects such as fragmentation, randomness and even disorientation in these paintings.

MS: Of course, the works themselves don’t fail as aesthetic objects: they are animated, complex and very rewarding. How do you navigate that in context of your stated concerns? I mean, is it okay to make a non-failing painting about failure?

JM: Thanks; I am glad you perceive them as ‘non-failing’, although of course not everyone would agree! It is a difficult question, but I guess I would argue that I am not deliberately trying to make a ‘bad’ painting

to illustrate failure. These paintings function in a space of disorientation, where they fall short of being fully representational of something concrete.

MS: The entropy, the endgame in which painting so often finds itself, seems expressed with so much fervour in this body of work. One senses a jangle of visual languages in works like Top Down and House of Cards, all competing for primacy; yet their organising principle is ‘the tendency for all matter and energy to evolve toward a state of inert uniformity’, as your statement for the show says.

JM: Yes, there is a lot of pushing and shoving going on! I feel that if I make the paintings very busy, if I keep filling them up with fragments, textures and competing colours, they may eventually topple over into a state of calmness. I feel I have not achieved that yet, but that is what I am aiming for. I like your analogy that there seems to be a competition for primacy. The visual language of advertising and product packaging somehow influences these works. I always find myself attracted to (and a bit repulsed by)

the bright pinks and yellows when walking down supermarket aisles. Information-overload is an underlying theme in these works.

MS: I want to pick up on this idea information-overload. I think one of the ways painting can respond well to the information flow that engulfs us is by slowing things down, enabling contemplation rather than just consumption. Does this idea filter into the way you deal with overload?

JM: I spend a lot of time just staring at my paintings, trying to figure them out. I see a certain value in the slow process often required to produce a painting or a body of work. For me it is almost like a performance piece (produced in the solitary confines of the studio) that counters our fast way of living. I think one of the enigmas of certain artworks is the ability to transcend time and trends.

MS: I always feel that artists who don’t acknowledge some sort of weight of history are foolish or deluded. As a young writer I would often play this game of dropping in obvious references that artists were looking at, hoping to catch them out on some level. Your work, by contrast, feels completely different: consciously immersed in a dialogue with visual culture of all sorts. How does the material of art’s history manifest for you when you’re in the studio?

JM: I began my studies at the University of Stellenbosch with Graphic Design and changed to Fine Arts after two years. That was in the beginning of the nineties just on the cusp of political change. Deconstruction was the buzzword and everywhere artists and students were juxtaposing things to break down old ideas or create new ways of looking. It was a time of ‘cutting and pasting’. As a student I always enjoyed looking at the early photomontage artists such as Hannah Höch, John Heartfield and the designs of the Russian Constructivists. I have always responded to art that has a strong graphic quality.

It is quite interesting that although this body of work is abstract, I have never really felt a great affinity with abstract painting. I have always been more influenced by figurative painters. This body of work developed through sheer frustration with my own figurative representation. I felt I needed to interact with the canvas on a more subconscious level, free from the restrictions of representation.

MS: What sort of process do you undergo: I would imagine the gestural areas and allusions to landscape and architecture are done in the initial stages, while the graphic shards of colour are floated over the top? Or how would you describe it?

JM: I have a ‘shoot from the hip’ approach when I start. I dive into the canvas with loose brush strokes. I start building onto this with more controlled shapes. At some stage I will break the picture down again

by ‘washing’ over it with a thin layer of paint. This creates depth and I start again with the layering, reacting to the residual marks and textures from before. It is a process of action and reaction. I heard [Cape Town- based sculptor and printmaker] Paul Edmunds mention that he creates a problem in his work and then likes to find ways to solve it. I can relate to that approach, but not in his meticulous way, of course.

MS: So do you use masking tape to mask off some areas that you want to keep while working on other areas that need to go further?

JM: Mostly I use the masking tape to create a ‘positive’ shape that will be painted on top of a previous layer. I like the very rigid, defined lines that the masking tape creates. My drawing teacher used to say that there is no such thing as a defined line and that everything is actually a blur!

MS: In works like Y, Rise and Fall and Bad Rhythm, there is even a suggestion that the coloured graphic elements are trying to form letters: some new, mutated language starts to emerge, and the works resemble posters with bold yet malfunctioning messages.

JM: As a graphic design student I always enjoyed the hand lettering projects. I think something of that discipline stayed with me and you are correct that parts of the paintings suggest lettering or typefaces. I like the idea of these paintings simulating the textural build-up often found on city walls and billboards caused by the multiple layering of posters. There is a certain beauty in the small fragments and leftovers of previous posters that were torn down.

MS: In Untitled, there is a strong suggestion of a portrait; previous works and shows have foregrounded your interest in painting people in rather more traditional manners. How does your previous history sit with this current mode of production?

JM: Yes, well spotted. It was actually an unfinished painting over which I worked. I think there are similarities in the application of paint and also my drawing mediums of charcoal and ink. The process of layering and ‘scraping’ is always there. I do have different modes of production as you call it. At the moment I am preoccupied with a more abstract approach to painting. This does not mean I have abandoned figurative work. I have always liked Daniel Richter’s seamless ability to move between figurative and abstract modes of painting. At some stage I would like to see if I am able to integrate these different approaches to painting.